Food Dishes That Start with K: A Culinary Journey

Introduction

Cuisine mirrors the soul of a community, blending history, landscape, and tradition on a single plate. Dishes whose names begin with the letter “K” are no exception: they can be fiery or mellow, humble or celebratory, yet each carries a story worth tasting. This brief tour highlights some of the most beloved “K” foods, tracing their roots and explaining why they continue to charm diners everywhere.

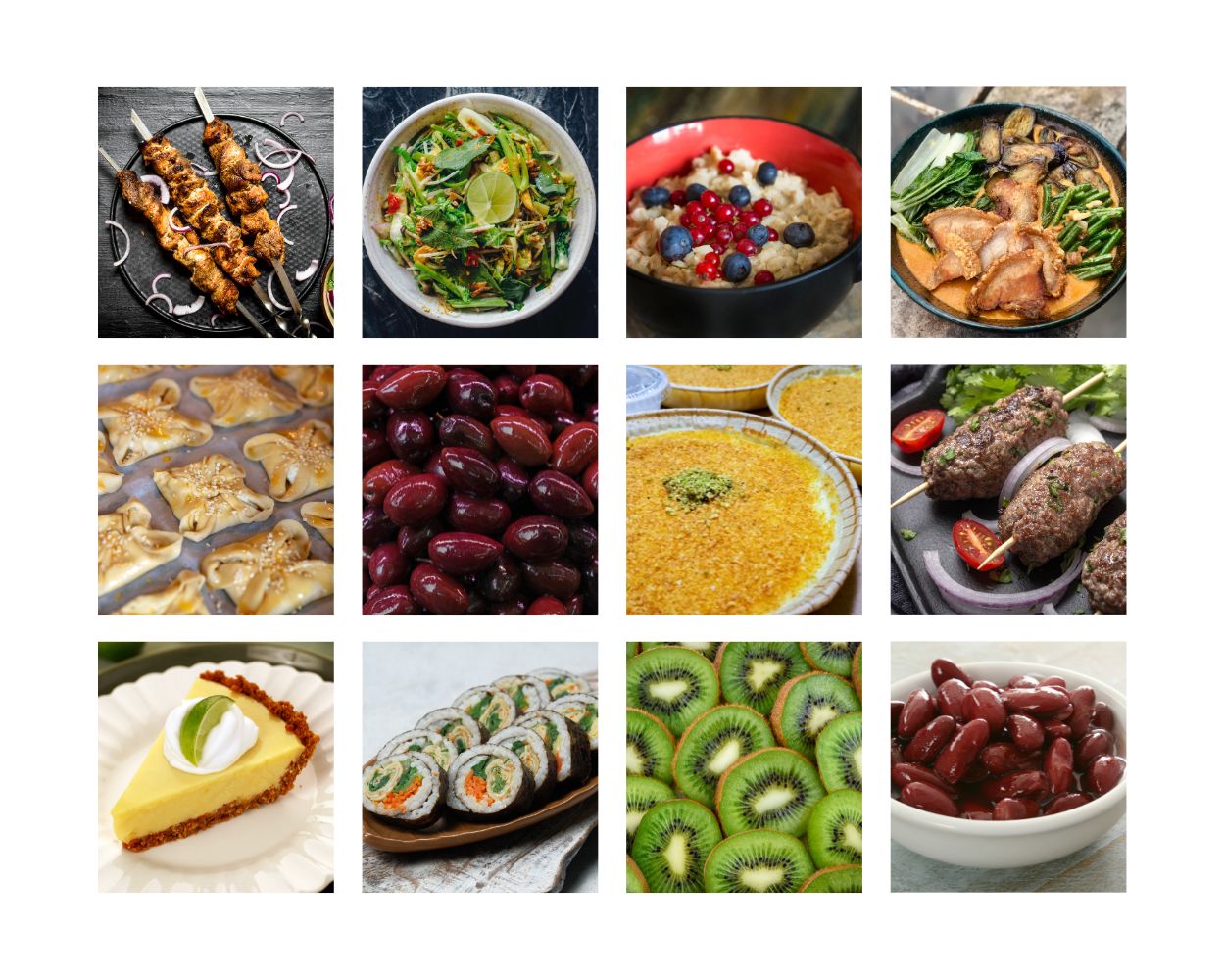

Korean Kimchi

Korean Kimchi

Kimchi is Korea’s iconic medley of salted and fermented vegetables—usually napa cabbage and daikon radish—brightened by chili, garlic, and ginger. The slow fermentation deepens flavor while boosting beneficial bacteria, making the dish as nutritious as it is addictive.

Early versions appeared centuries ago as a practical way to keep vitamins within reach during long winters. Over generations, each province refined its own ratio of heat, tang, and sweetness, turning preservation into an art form.

Today kimchi is served at almost every Korean meal, folded into fried rice, layered on noodles, or simply offered solo in small plates called banchan. Its lively crunch and probiotic punch have also earned it fans far beyond the peninsula.

Kenyan Kachumbari

Kenyan Kachumbari

Kachumbari is East Africa’s answer to pico de gallo: diced tomatoes, onions, and mild chilies tossed with lemon and a whisper of cilantro. The salad’s bright acidity cuts through rich stews and grilled meats, making it a staple at both roadside kiosks and family feasts.

Coastal communities first mixed the dish from garden surplus, but word traveled inland along trade routes. Now, whether paired with cornmeal ugali or spooned over charcoal-roasted fish, kachumbari signals freshness and hospitality in equal measure.

Its simplicity invites improvisation—avocado for creaminess, mango for sweetness—yet the core trio of tomato, onion, and citrus remains a unifying national accent.

Kazakh Kazy

Kazakh Kazy

Kazy is a rustic horse-milk product gently fermented until it thickens into a tangy, slightly effervescent drink. Nomadic herders discovered that the natural sugars in mare’s milk transform into pleasant sourness when kept in skin pouches on long treks across the steppe.

Shared from carved wooden bowls during weddings and spring festivals, kazy embodies generosity and endurance. Modern enthusiasts chill it for a refreshing sip or blend it into light soups, continuing a tradition that predates the Silk Road.

Beyond flavor, the living cultures in kazy are prized for aiding digestion after protein-heavy meals of dried meats and flatbreads.

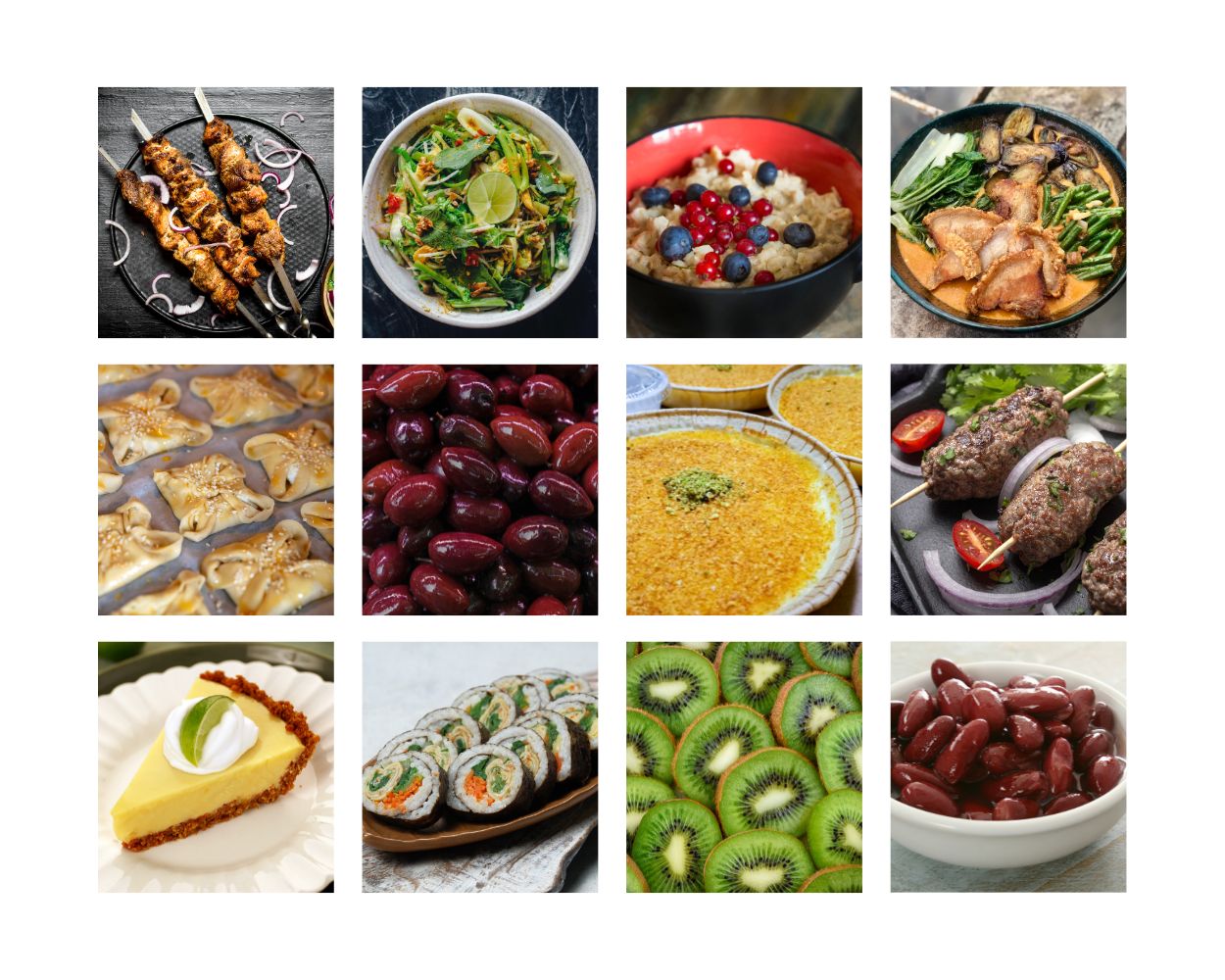

Korean Kimchi Jjigae

Korean Kimchi Jjigae

Kimchi jjigae turns older, sharper kimchi into a bubbling red stew fortified with tofu, pork, or tuna. Anchovy broth and a dab of fermented bean paste round out the heat, creating layers of umami that steam away winter chills.

Historically, households stretched precious protein by simmering it with rice-water and yesterday’s kimchi, yielding a pot hearty enough to feed an extended family. The technique endures because it rewards patience: the longer the stew murmurs on the stove, the deeper the marriage of spice and smoke.

Served straight from the earthenware pot with a ladle of fluffy white rice, kimchi jjigae remains Korea’s ultimate comfort bowl—proof that yesterday’s side dish can become today’s centerpiece.

Conclusion

From the piquant crunch of kimchi to the sun-kissed zest of kachumbari and the tart sparkle of kazy, “K” foods invite us to explore new textures and temperatures without leaving our kitchens. They remind us that every ingredient carries a passport: fermented, chopped, or gently soured by human ingenuity across continents.

So the next time you spot a recipe beginning with “K,” give it a try; each bite is a small, edible postcard from someone else’s tradition, delivered directly to your table.